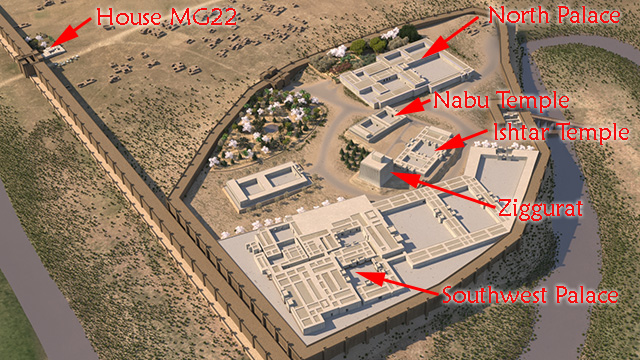

The North Palace of King Ashurbanipal (reigned 668-627 BCE) is so named due to its location on the Nineveh citadel mound of Kuyunjik (see its location on the aerial view at the left; hover over to enlarge). He (re)built the palace beginning about 646 BCE after the Assyrian army defeated long-established regional opponents and captured the cities of Babylon in southern Iraq and Susa in southern Iran. Ashurbanipal called his new building a bit riduti according to foundation tablets found under the palace. Although the term is somewhat ambiguous in meaning and usage, it normally refers to a crown prince's palace (which is odd, since Ashurbanipal was already king; but it may refer to the fact that a previous building on the site was used by him or his predecessors when not yet in power). The palace was most likely completed in 643 BCE, as wall relief scenes do not show any events that took place after this date. The North Palace, however, had a short life as it was burned in 612 BC, presumably during the sack of Nineveh by the Babylonians.

The North Palace of King Ashurbanipal (reigned 668-627 BCE) is so named due to its location on the Nineveh citadel mound of Kuyunjik (see its location on the aerial view at the left; hover over to enlarge). He (re)built the palace beginning about 646 BCE after the Assyrian army defeated long-established regional opponents and captured the cities of Babylon in southern Iraq and Susa in southern Iran. Ashurbanipal called his new building a bit riduti according to foundation tablets found under the palace. Although the term is somewhat ambiguous in meaning and usage, it normally refers to a crown prince's palace (which is odd, since Ashurbanipal was already king; but it may refer to the fact that a previous building on the site was used by him or his predecessors when not yet in power). The palace was most likely completed in 643 BCE, as wall relief scenes do not show any events that took place after this date. The North Palace, however, had a short life as it was burned in 612 BC, presumably during the sack of Nineveh by the Babylonians.

In December 1853, the North Palace was rediscovered by a team excavating the Nineveh citadel under the auspices of the British Museum. The team was led by Henry Rawlinson, their local in charge, but fieldwork was directed by Hormuzd Rassam. Carved wall reliefs from the palace were shipped to the British Museum. Excavations continued by various people on and off for the next decade or so; yet only a small portion of the building has been exposed, despite further clearings into the early 20th century. The main floor-level of the palace was not far below the modern surface of the mound, and much of the building had already been destroyed by erosion and later occupation. (Barnett 1976; Kertai 2015; Reade 1998-2001:416-18).

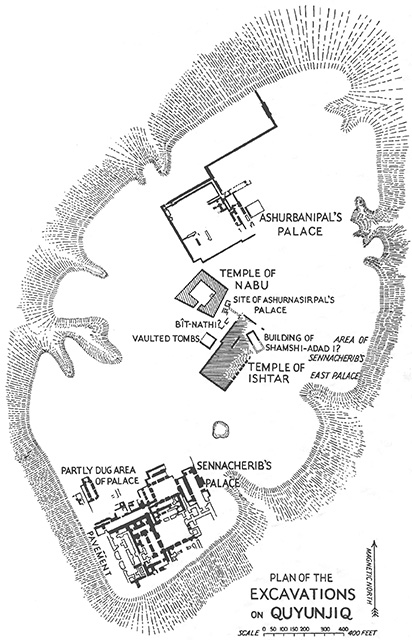

After 175 years of investigation, the North Palace remains incompletely excavated (see the 1934 Campbell Thompson plan at the left, where it is labeled "Ashurbanipal's Palace" (Barnett et al. 1998:plate 5; hover over to enlarge). Probably less than half has been uncovered. Thus, the plan is poorly understood even across the excavated southwestern sections, and not at all understood to the northeast. The exposed area shows the palace to be at minimum 120m wide; its original length is unknown, but it was at least 250m based on excavated remains (it was considerably smaller than the Southwest Palace; see the citadel reconstruction above). If there had been a previous structure on this site, Ashurbanipal seems to have destroyed it (or any earlier remains have not yet been clearly identified).

After 175 years of investigation, the North Palace remains incompletely excavated (see the 1934 Campbell Thompson plan at the left, where it is labeled "Ashurbanipal's Palace" (Barnett et al. 1998:plate 5; hover over to enlarge). Probably less than half has been uncovered. Thus, the plan is poorly understood even across the excavated southwestern sections, and not at all understood to the northeast. The exposed area shows the palace to be at minimum 120m wide; its original length is unknown, but it was at least 250m based on excavated remains (it was considerably smaller than the Southwest Palace; see the citadel reconstruction above). If there had been a previous structure on this site, Ashurbanipal seems to have destroyed it (or any earlier remains have not yet been clearly identified).

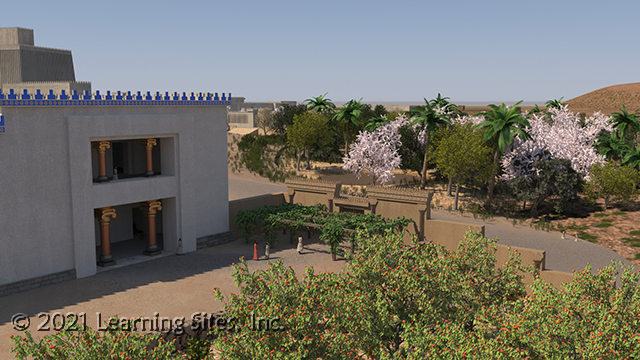

The North Palace is both a fairly typical Assyrian palace in the type and arrangement of suites, and also unique in its details and constructed to fit the location on the citadel (see Learning Sites reconstruction at the left, view north over the palace; hover over to enlarge). According to his writings, Ashurbanipal raised the palace on a 6m-high platform; careful not to go higher lest it surpass the mounds of nearby temple precincts.

The North Palace is both a fairly typical Assyrian palace in the type and arrangement of suites, and also unique in its details and constructed to fit the location on the citadel (see Learning Sites reconstruction at the left, view north over the palace; hover over to enlarge). According to his writings, Ashurbanipal raised the palace on a 6m-high platform; careful not to go higher lest it surpass the mounds of nearby temple precincts.

The main courtyard (designated 'O' by the excavators) was entered (via a short ramp up) from the citadel grounds (bottom center in the rendering at the left; hover over to enlarge). It, in turn, led and gave access to the throne-room courtyard. The throne room suite was entered via a series of steps (an unusual feature for a major Assyrian building facade). The throne room (designated 'M' on plans) has wall reliefs depicting battles against several major Assyrian enemies. Similar battle scenes along with hunting scenes are found on most rooms of the palace.

The main courtyard (designated 'O' by the excavators) was entered (via a short ramp up) from the citadel grounds (bottom center in the rendering at the left; hover over to enlarge). It, in turn, led and gave access to the throne-room courtyard. The throne room suite was entered via a series of steps (an unusual feature for a major Assyrian building facade). The throne room (designated 'M' on plans) has wall reliefs depicting battles against several major Assyrian enemies. Similar battle scenes along with hunting scenes are found on most rooms of the palace.

One inner courtyard (designated 'J' and located behind the throne room suite) was most likely surrounded by administrative and private family suites on its other three sides but the precise configuration of each is speculative. One suite probably incorporated a bit hilani (building or section of building designed in the Syro-Hittite style) with bronze-covered columns at the entrance (on the left far side of Couryard O in the rendering at the left; hover over to enlarge).

One inner courtyard (designated 'J' and located behind the throne room suite) was most likely surrounded by administrative and private family suites on its other three sides but the precise configuration of each is speculative. One suite probably incorporated a bit hilani (building or section of building designed in the Syro-Hittite style) with bronze-covered columns at the entrance (on the left far side of Couryard O in the rendering at the left; hover over to enlarge).

At the back of the palace is a long sloping passage, with lion hunt scenes lining its walls, leading down to Room 'S' which had a wide columned postern entry space open to the lower side of the citadel (see the view at the left; hover over to enlarge). Somewhere, according to ancient texts, near or beside the palace was an orchard (we have added one out here behind the palace and off to the southwest, clearly visible by inhabitants from the bit hilani suite off the inner courtyard (see the aerial renderings above).

At the back of the palace is a long sloping passage, with lion hunt scenes lining its walls, leading down to Room 'S' which had a wide columned postern entry space open to the lower side of the citadel (see the view at the left; hover over to enlarge). Somewhere, according to ancient texts, near or beside the palace was an orchard (we have added one out here behind the palace and off to the southwest, clearly visible by inhabitants from the bit hilani suite off the inner courtyard (see the aerial renderings above).

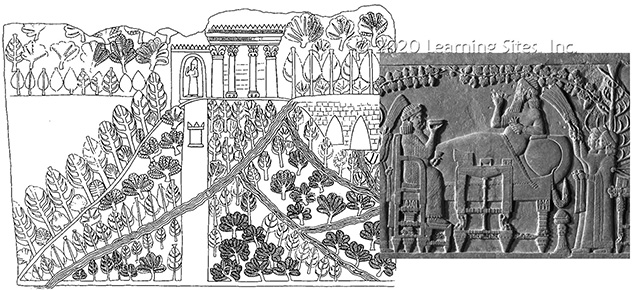

We know from Ashurbanipal's writings and reliefs found throughout the palace, that he liked gardens (he tells us that he planted almonds, dates, ebony, rosewood, olive, oak, tamarisk, walnut, terebinth, ash, fir, pomegranate, pear, quince, fig, and grapevines). He and his queen are even depicted having a picnic outside under an arbor (see the two scenes at the left from reliefs in the palace; one showing a garden and the other outdoor dining; hover over to enlarge).

We know from Ashurbanipal's writings and reliefs found throughout the palace, that he liked gardens (he tells us that he planted almonds, dates, ebony, rosewood, olive, oak, tamarisk, walnut, terebinth, ash, fir, pomegranate, pear, quince, fig, and grapevines). He and his queen are even depicted having a picnic outside under an arbor (see the two scenes at the left from reliefs in the palace; one showing a garden and the other outdoor dining; hover over to enlarge).

We have reconstructed a rear garden arbor and gate, to reflect what is seen in the reliefs, out behind the palace in a private area near the postern entry Room 'S' (see the two renderings at the left; hover over to enlarge).

We have reconstructed a rear garden arbor and gate, to reflect what is seen in the reliefs, out behind the palace in a private area near the postern entry Room 'S' (see the two renderings at the left; hover over to enlarge).

A detail of the arbor setting, with the queen and her guards out for a stroll.

A detail of the arbor setting, with the queen and her guards out for a stroll.

Barnett, Richard D.

1976 Sculptures from the North Palace of Ashurbanipal at Nineveh (668 - 627 B.C.). London: Trustees of the British Museum; British Museum Publications.

Barnett, Richard D.; Erika Bleibtreu and Geoffrey Turner

1998 Sculptures from the Southwest Palace of Sennacherib at Nineveh. London: Trustees of the British Museum, British Museum Press (2 vols.).

Kertai, David

2015 The Architecture of Late Assyrian Royal Palaces. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

2013 "The Multiplicity of Royal Palaces: how many palaces did an Assyrian king need?" pp.11-22 in David Kertai and Peter A. Miglus, eds., New Research on Assyrian Palaces. Heidelberger Studien zum Alten Orient v.15.

Petit, L. P. & D. Morandi Bonacossi

2017 Nineveh: the great city, symbol of beauty and power. Papers on Archaeology of the Leiden Museum of Antiquities vol. 13. Leiden: Sidestone Press.

Reade, Julian Edgeworth

2018 "Ashurbanipal's Palace at Nineveh," pp.20-33 in Gareth Brereton, ed., I am Ashurbanipal: king of the world, king of Assyria. London: Thames & Hudson and the British Museum.

2009 "Understanding the North Palace at Nineveh," unpublished paper delivered at a conference in Mainz on May 12.

1998-2001 "Ninive (Nineveh)," v.9, pp.388-433 in Erich Ebeling, Dietz Otto Edzard, Gabriella Frantz-Szabó, Bruno Meissner, Wolfram von Soden, and Ernst Weidner, eds. Reallexikon der Assyriologie und Vorderasiatischen Archäologie. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter.

1996 "Nineveh," pp.152-70 in Joan Goodnick Westenholz, ed., Royal Cities of the Biblical World. Jerusalem: Buble Lands Museum.