From the mid-1800s, when archaeologist Austin Henry Layard produced the first illustrations reconstructing the Northwest Palace at Nimrud (see Layard's representation of a Neo-Assyrian throne room at the left; plate II in his 1849 publication; hover over to enlarge), to today’s computer-generated 3D models of the palace, no woman has ever been represented in the royal environment (below, Learning Sites' reconstruction of the throne room from the Northwest Palace; hover over to enlarge).

From the mid-1800s, when archaeologist Austin Henry Layard produced the first illustrations reconstructing the Northwest Palace at Nimrud (see Layard's representation of a Neo-Assyrian throne room at the left; plate II in his 1849 publication; hover over to enlarge), to today’s computer-generated 3D models of the palace, no woman has ever been represented in the royal environment (below, Learning Sites' reconstruction of the throne room from the Northwest Palace; hover over to enlarge).

Indeed, the Neo-Assyrian palace has been presented, rather inadvertently, as a man’s world. The absence of women in modern reconstructions likely stems from a lack of understanding of the important roles that women played in royal culture and to a dearth of evidence for what royal Neo-Assyrian females would have looked like. However, it is time to update our perceptions of history! Recent scholarship on Neo-Assyrian queens debunks old-fashioned visions of harems and, instead, establishes that royal women engaged in economic, diplomatic, and ritual activities. Within the palace, queens had their own scribes, managed their own households, and were vital counterparts to the king’s identity and authority.

Indeed, the Neo-Assyrian palace has been presented, rather inadvertently, as a man’s world. The absence of women in modern reconstructions likely stems from a lack of understanding of the important roles that women played in royal culture and to a dearth of evidence for what royal Neo-Assyrian females would have looked like. However, it is time to update our perceptions of history! Recent scholarship on Neo-Assyrian queens debunks old-fashioned visions of harems and, instead, establishes that royal women engaged in economic, diplomatic, and ritual activities. Within the palace, queens had their own scribes, managed their own households, and were vital counterparts to the king’s identity and authority.

There is actually a good deal of information about what a Neo-Assyrian queen would have looked like. A handful of large- and small-scale artworks, including miniature figures carved on a pendant and seals dating to the 9th to 8th centuries BCE (such as the gold stamp seal belonging to Queen Hamâ [Iraq Museum 115644], found in Coffin 2 of Tomb III at Nimrud) and a palace relief and stele portraying King Ashurbanipal’s 7th-century BCE queen, Liballi-sharrat (as seen in the banquet depicted on a relief sculpture from the North Palace at Nineveh [BM 124920]), document general consistencies in the queen’s image over the course of centuries. The queen is depicted wearing a curly hairstyle (similar to the king’s), a long dress, a headdress, and, in some images, various items of jewelry.

Additional evidence for the queen’s appearance can be drawn from the headdresses and hundreds of pieces of jewelry preserved in the tombs of 9th- and 8th-century BCE queens excavated from beneath the Northwest Palace (headdress from Nimrud’s Tomb II [Iraq Museum 105696]) at the left; image courtesy of Amy Gansell; hover over to enlarge).

Additional evidence for the queen’s appearance can be drawn from the headdresses and hundreds of pieces of jewelry preserved in the tombs of 9th- and 8th-century BCE queens excavated from beneath the Northwest Palace (headdress from Nimrud’s Tomb II [Iraq Museum 105696]) at the left; image courtesy of Amy Gansell; hover over to enlarge).

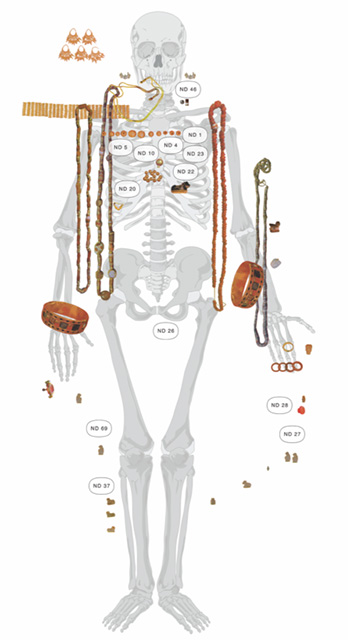

We can infer that the dead were dressed in ensembles similar to what they wore in life, because several pieces of jewelry from the tombs match items depicted on figures in art (drawing at the left showing the layout of items found on the skeleton in Tomb I's coffin at Nimrud; image © and courtesy A. R. Gansell and J. Pope; hover over the enlarge). No intact garments survived in the tombs, but remnants of fabric indicate that supple undyed linens were used.

We can infer that the dead were dressed in ensembles similar to what they wore in life, because several pieces of jewelry from the tombs match items depicted on figures in art (drawing at the left showing the layout of items found on the skeleton in Tomb I's coffin at Nimrud; image © and courtesy A. R. Gansell and J. Pope; hover over the enlarge). No intact garments survived in the tombs, but remnants of fabric indicate that supple undyed linens were used.

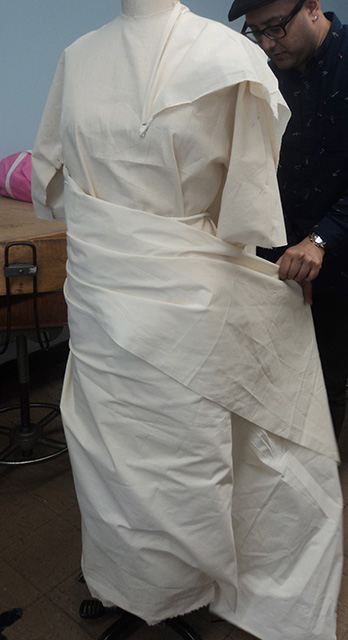

Efforts to reconstruct a queenly garment began at the Fashion Institute of Technology in 2012 with draping experiments on a dress form, under the direction of Amy Gansell. These forays into experimental archaeology took into account consideration images of garments in art, the location of fibulae on the queens’ skeletons, and the distribution of ornaments and textiles remnants preserved in their coffins (sample view of the live garment testing at the left; image © and courtesy of Amy Gansell; hover over to enlarge).

Efforts to reconstruct a queenly garment began at the Fashion Institute of Technology in 2012 with draping experiments on a dress form, under the direction of Amy Gansell. These forays into experimental archaeology took into account consideration images of garments in art, the location of fibulae on the queens’ skeletons, and the distribution of ornaments and textiles remnants preserved in their coffins (sample view of the live garment testing at the left; image © and courtesy of Amy Gansell; hover over to enlarge).

Learning Sites was called in to help continue the investigation of royal garment design and to help test hypotheses not otherwise easy to accomplish outside the realm of 3D modeling (the current iteration of our testing at the left; hover over to enlarge). Information about the heights (on average, between about 5’1” and 5’2”), ages (between about 20 and 55), and body types (ranging from slim to full-figured) of Neo-Assyrian queens is available from studies conducted on the bones in their coffins. The 3D queen’s physique, facial characteristics, hairstyle, and clothing are primarily inspired by images of queens in Assyrian art. Her adornment is proportioned and arranged according to archaeological records. She is wearing a combination of items from Nimrud’s Tombs I and II. Although 7th-century BCE images of Neo-Assyrian queens depict them wearing a crown of city walls, no headdress of this variety was discovered in the Nimrud tombs. Because Learninig Sites' virtual reality palace model is intended to represent the palace during the era of its first ruler, Ashurnasirpal II (883-859 BCE), a headdress from a tomb that is closer in date to this era was selected.

Learning Sites was called in to help continue the investigation of royal garment design and to help test hypotheses not otherwise easy to accomplish outside the realm of 3D modeling (the current iteration of our testing at the left; hover over to enlarge). Information about the heights (on average, between about 5’1” and 5’2”), ages (between about 20 and 55), and body types (ranging from slim to full-figured) of Neo-Assyrian queens is available from studies conducted on the bones in their coffins. The 3D queen’s physique, facial characteristics, hairstyle, and clothing are primarily inspired by images of queens in Assyrian art. Her adornment is proportioned and arranged according to archaeological records. She is wearing a combination of items from Nimrud’s Tombs I and II. Although 7th-century BCE images of Neo-Assyrian queens depict them wearing a crown of city walls, no headdress of this variety was discovered in the Nimrud tombs. Because Learninig Sites' virtual reality palace model is intended to represent the palace during the era of its first ruler, Ashurnasirpal II (883-859 BCE), a headdress from a tomb that is closer in date to this era was selected.

The 3D model of the queen is shown here holding a stamp seal (depicted, based on archaeological evidence, connected to her garment by a chain attached to a fibula; hover over to enlarge) to reinforce the active roles that women played in the Neo-Assyrian court.

The 3D model of the queen is shown here holding a stamp seal (depicted, based on archaeological evidence, connected to her garment by a chain attached to a fibula; hover over to enlarge) to reinforce the active roles that women played in the Neo-Assyrian court.

The creation of the 3D computer model of a Neo-Assyrian queen was supported by a Seed Grant from St. John’s University (2016). A research grant from The American Academic Research Institute in Iraq (TAARI) supported the research on garment draping conducted at the State University of New York’s (SUNY) Fashion Institute of Technology (2012-2013). The text here has been graciously supplied by Amy Gansell. Pending funding, the 3D model of the queen will be added to the Northwest Palace virtual world, offering a more balanced conception of men’s and women’s contributions to Neo-Assyrian royal culture.

Gansell, A. R.

2013 “Images and Conceptions of Ideal Feminine Beauty in Neo-Assyrian Royal Contexts,” pp.391-420 in M. Feldman and B. Brown, eds. Critical Approaches to Ancient Near Eastern Art. Boston: de Gruyter.

2007 "From Mesopotamia to Modern Syria: Ethno-archaeological Perspectives on Female Adornment During Rites of Passage," pp. 449-83, in M. Feldman and J. Cheng, eds. Ancient Near Eastern Art in Context, Festschrift Irene J. Winter. Boston: Brill.

Hussein, M. M.

2016 Nimrud: The Queens’ Tombs, M. Gibson, de., trans. by M. Altaweel. Chicago: Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago.

Kertai, D.

2013 “The Queens of the Neo-Assyrian Empire.” Altorientalische Forschungen 40:108-24.

Macgregor, S. L.

2012 Beyond Hearth and Home: Women in the Public Sphere in Neo-Assyrian Society. Issue 5 of Publications of the Foundation for Finnish Assyriological Research and Volume 21 of State Archives of Assyria Studies.

Melville, S. C.

1999 The Role of Naqia/Zakutu in Sargonid Politics. Volume 9 of State Archives of Assyria Studies. Helsinki: the Neo-Assyrian Text Corpus Project.

Solvang, E. K. M.

2006 “Another Look ‘Inside’: Harems and the Interpretation of Women,” pp.374-98 S. Holloway, ed. Orientalism, Assyriology and the Bible. Sheffield, England: Sheffield Phoenix Press.

Svärd, S.

2015 Women and Power in Neo-Assyrian Palaces.

Helsinki: University of Helsinki.