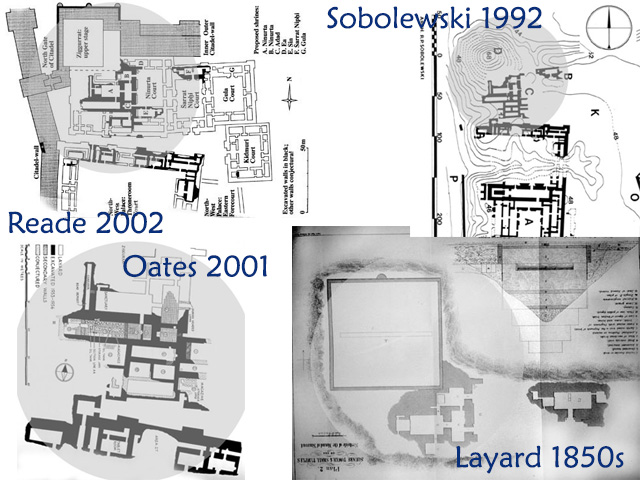

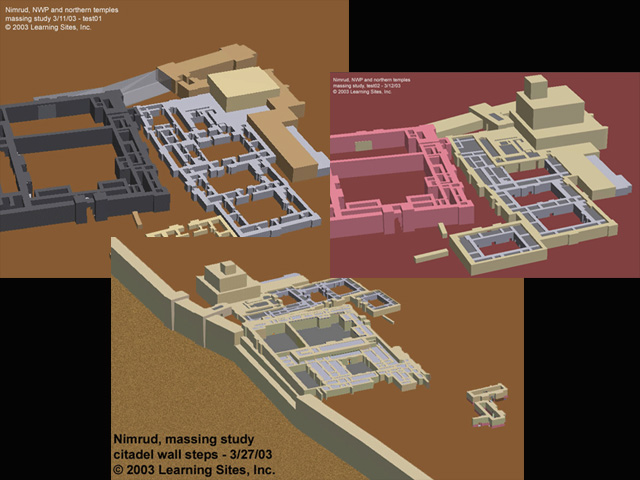

Since 1998, we have been building a virtual reality (VR) model of the citadel at Nimrud, originally constructed by the ninth-century BC Assyrian King Ashurnasirpal II (see the map of Assyrian capital cities at the left; hover over to enlarge). We began with Ashurnasirpal's palace, the so-called Northwest Palace, and have now expanded to include the area of the eighth-century-BC so-called Central Palace of Tiglath-pileser III, as well as the temples and ziggurat in the northern part of the citadel (see the Nimrud citadel site plan at the left; hover over to enlarge). The evidence of ancient occupation is detailed enough to have embarked on the construction of a full-scale interactive VR model.

Since 1998, we have been building a virtual reality (VR) model of the citadel at Nimrud, originally constructed by the ninth-century BC Assyrian King Ashurnasirpal II (see the map of Assyrian capital cities at the left; hover over to enlarge). We began with Ashurnasirpal's palace, the so-called Northwest Palace, and have now expanded to include the area of the eighth-century-BC so-called Central Palace of Tiglath-pileser III, as well as the temples and ziggurat in the northern part of the citadel (see the Nimrud citadel site plan at the left; hover over to enlarge). The evidence of ancient occupation is detailed enough to have embarked on the construction of a full-scale interactive VR model.

The model is being built on both PC and Onyx platforms for distance learning across the Internet (see a view of the Onyx VR station at the left, showing a user with 3D glasses; and the PC version demonstrated at the AIA meetings in 2003; hover over to enlarge). Versions of the model can be viewed on the Learning Sites and University at Buffalo Virtual Site Museum's Web pages (ed. note 9/2019: the University at Buffalo Web page is no longer active).

The model is being built on both PC and Onyx platforms for distance learning across the Internet (see a view of the Onyx VR station at the left, showing a user with 3D glasses; and the PC version demonstrated at the AIA meetings in 2003; hover over to enlarge). Versions of the model can be viewed on the Learning Sites and University at Buffalo Virtual Site Museum's Web pages (ed. note 9/2019: the University at Buffalo Web page is no longer active).

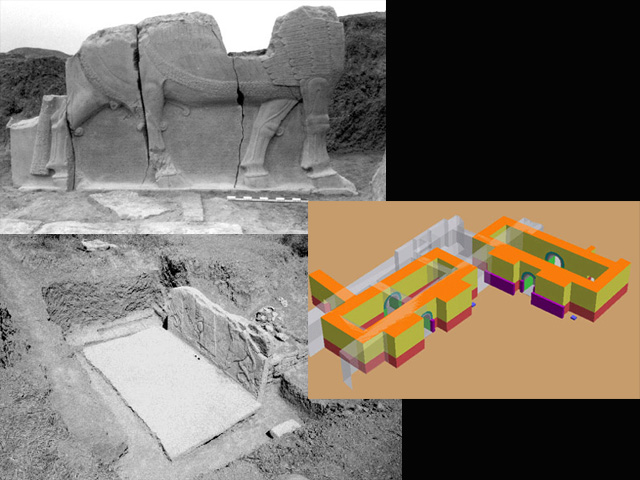

The deteriorating state of preservation at the site and the looting of its storerooms after the Gulf War of 1991-2, the subsequent UN sanctions which made site conservation difficult placing many of its monuments in jeopardy, the further looting of two pieces of bas-relief from the palace museum’s wall and the damage to several others last spring after Operation Iraqi Freedom, have made it extremely important that we continue to forge ahead to continue the digital documentation of Nimrud (see the two examples of such damage at the left; one to the arms of a lamassu, photo courtesy of Michael Weigl; the other looting of wall relief fragments, photo courtesy of Mark Altaweel; hover over to enlarge). We intend that this record will become one of the main resources for the preservation of Nimrud as a historical site and assist in its reconstruction as a site museum. This documentation will be available on the World Wide Web. The Website will detail the state of preservation and conservation at different periods of the site’s modern history, will assist in the recovery of stolen objects through the publication of all relevant published and unpublished material in one place, and will contribute to the future history of the site by creating a resource for the study of the history and culture of this ancient Assyrian capital.

The deteriorating state of preservation at the site and the looting of its storerooms after the Gulf War of 1991-2, the subsequent UN sanctions which made site conservation difficult placing many of its monuments in jeopardy, the further looting of two pieces of bas-relief from the palace museum’s wall and the damage to several others last spring after Operation Iraqi Freedom, have made it extremely important that we continue to forge ahead to continue the digital documentation of Nimrud (see the two examples of such damage at the left; one to the arms of a lamassu, photo courtesy of Michael Weigl; the other looting of wall relief fragments, photo courtesy of Mark Altaweel; hover over to enlarge). We intend that this record will become one of the main resources for the preservation of Nimrud as a historical site and assist in its reconstruction as a site museum. This documentation will be available on the World Wide Web. The Website will detail the state of preservation and conservation at different periods of the site’s modern history, will assist in the recovery of stolen objects through the publication of all relevant published and unpublished material in one place, and will contribute to the future history of the site by creating a resource for the study of the history and culture of this ancient Assyrian capital.

The Central Palace part of the project is also the comprehensive final report of the Polish Center of Archaeology's excavations in the area of the Central Palace (1973 - 1976), supported with by a Levy-White grant from Harvard University.

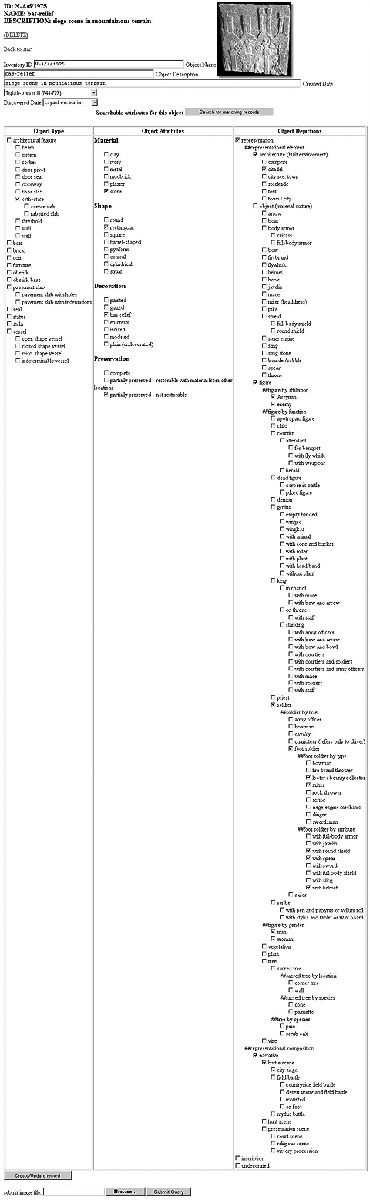

We began the project with Ashurnasirpal’s palace since it was one of the best-preserved monuments on the site. We have over 150 years of various kinds of documentation just for this building alone. We have expanded our computer model to include the temple area north of the palace and the area just south of it, where two other buildings, one of Ashurnasirpal and one of his son, Shalmaneser III (late 9th c. BC), were found, and where the bas-reliefs from a very much destroyed (8th c. BC) palace of King Tiglath-pileser III were located. It was from this area that many of the bas-reliefs stolen from the site storerooms came. As money and time allow, we will eventually complete the reconstruction of the whole citadel. On the Web pages we have broken down the categories of information to include not only the VR models with the reasoning behind the model’s structures, but also the history of the excavation and photographic documentation of the excavation, conservation, and the present state of preservation.