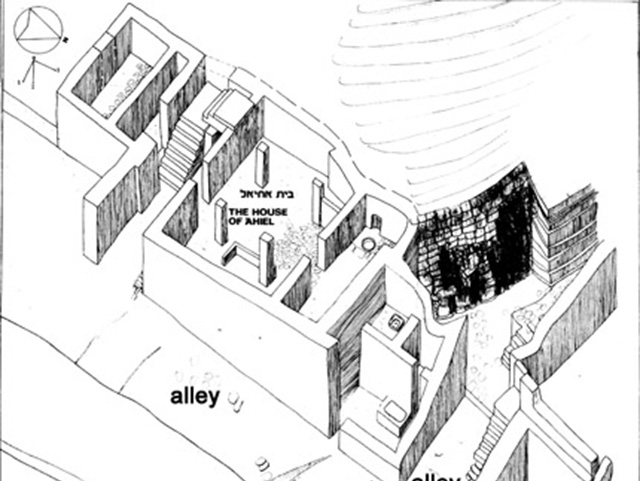

The core team of the two companies that I run (the Institute for the Visualization of History & Learning Sites, Inc.) is the oldest continually operating group active in the field known as virtual heritage--that is, using interactive computer graphics for the collection, study, teaching, publication, display, and broadcast of information about the past (see a sampling of our projects at the left; hover over to enlarge). We are archaeologists, art historians, architectural historians, and information scientists working with programmers and computer graphic artists.

The core team of the two companies that I run (the Institute for the Visualization of History & Learning Sites, Inc.) is the oldest continually operating group active in the field known as virtual heritage--that is, using interactive computer graphics for the collection, study, teaching, publication, display, and broadcast of information about the past (see a sampling of our projects at the left; hover over to enlarge). We are archaeologists, art historians, architectural historians, and information scientists working with programmers and computer graphic artists.

Among other things, we have been providing museums with innovative visual content for over 10 years (see the sample listings at the left; hover over to enlarge).

Among other things, we have been providing museums with innovative visual content for over 10 years (see the sample listings at the left; hover over to enlarge).

And we've collaborated with curators and educators at such institutions as Old Sturbridge Village and Germantown, Pennsylvania, the British Museum, the Miho Museum, the Oriental Institute Museum, the University of Pennsylvania Museum, and the Petrie Museum. Our projects include digital reconstructions based on architectural fragments in museum collections, putting objects from galleries back into simulations of their original contexts, assisting in staff research projects, and developing outreach materials.

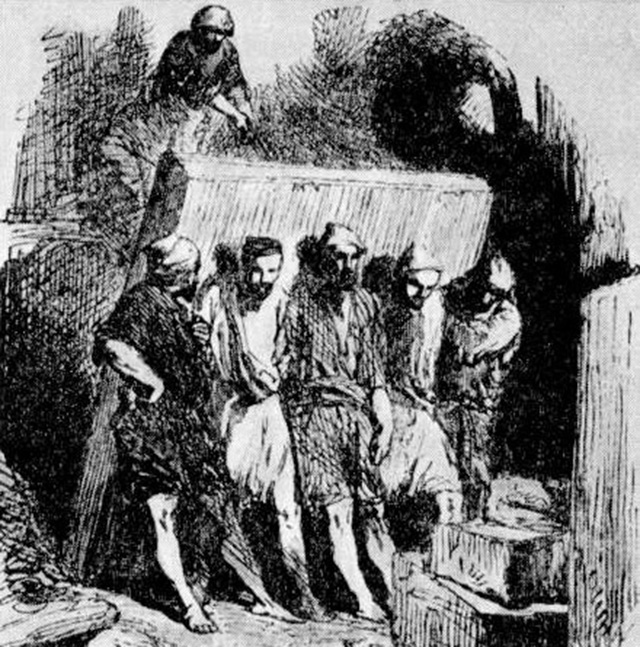

3D computer graphics offer many advantages for conveying alternate realities for museum visitors; of providing them with portholes to the past (see the aerial rendering of Nemrud Dagi, Turkey, at the left; from the Learning Sites virtual reality model of the site; hover over to enlarge). Not simply pretty pictures, but instead imparting engaging adventures, personalized experiences, and contextual interpretations of the items displayed before them. 3D computer graphics can tell stories, inform, educate, engage, excite, and provide memorable experiences in ways not possible with traditional visualization modes or media; in ways that supplement and enhance other themed events and exhibits; with the goal of offering visitors a glimpse into what happened at an ancient or historic site, who some of the inhabitants were, and why visitors should return to the museum again and again.

3D computer graphics offer many advantages for conveying alternate realities for museum visitors; of providing them with portholes to the past (see the aerial rendering of Nemrud Dagi, Turkey, at the left; from the Learning Sites virtual reality model of the site; hover over to enlarge). Not simply pretty pictures, but instead imparting engaging adventures, personalized experiences, and contextual interpretations of the items displayed before them. 3D computer graphics can tell stories, inform, educate, engage, excite, and provide memorable experiences in ways not possible with traditional visualization modes or media; in ways that supplement and enhance other themed events and exhibits; with the goal of offering visitors a glimpse into what happened at an ancient or historic site, who some of the inhabitants were, and why visitors should return to the museum again and again.

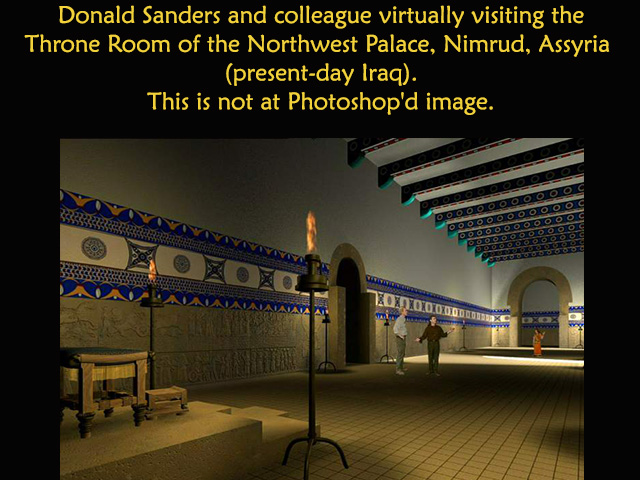

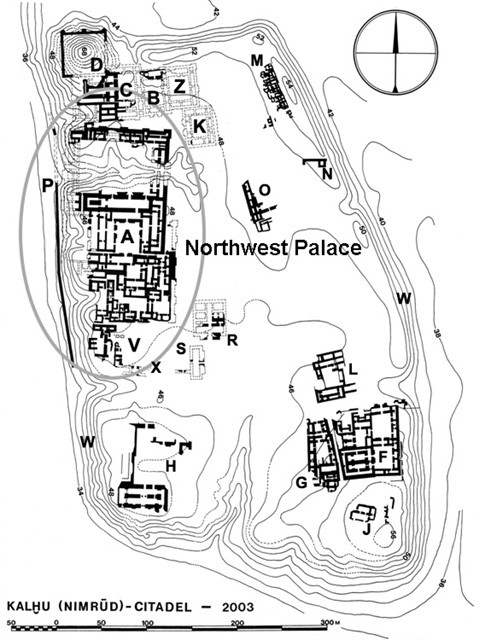

My topic today is the use of virtual reality in museums, such as our Virtual Site Museum (or VSM), a concept we developed collaboratively with the University of Buffalo (hover over the image at the left to enlarge). The VSM is a fully interactive, virtual environment for museum gallery visitors, educational and promotional outreach, and curatorial research. The virtual world contains precise, authoritative, and integrated archaeological and historical data culled from published and unpublished excavation records and holdings at various museums and archaeological sites. Objects in the virtual world are linked to 2D images, explanatory text, and online resources to produce an engaging and educational participatory experience. The resulting real-time module can be viewed either in full-body immersion or on gallery-based computer kiosks.

My topic today is the use of virtual reality in museums, such as our Virtual Site Museum (or VSM), a concept we developed collaboratively with the University of Buffalo (hover over the image at the left to enlarge). The VSM is a fully interactive, virtual environment for museum gallery visitors, educational and promotional outreach, and curatorial research. The virtual world contains precise, authoritative, and integrated archaeological and historical data culled from published and unpublished excavation records and holdings at various museums and archaeological sites. Objects in the virtual world are linked to 2D images, explanatory text, and online resources to produce an engaging and educational participatory experience. The resulting real-time module can be viewed either in full-body immersion or on gallery-based computer kiosks.