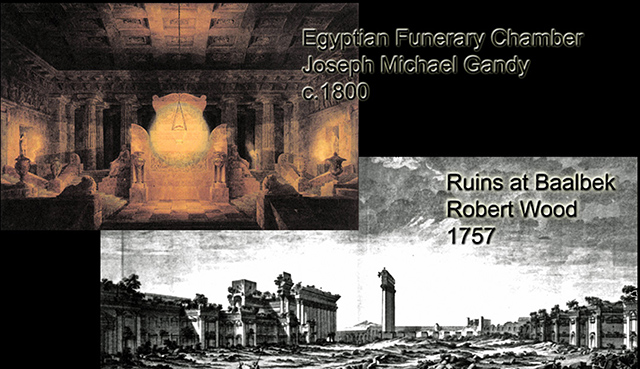

Understanding the distant past isn't easy; we weren't there! Archaeology (the study of the material culture of the past) emerged in the age of fine draftsmanship, meticulously refined renderings crafted slowly by hand, and equally elaborate prose (see sample 18th c. renderings at the left; hover over to enlarge). But that was centuries ago, and you don't see many people these days riding in horse-drawn carriages, writing books with quill pen, or finding their way by candlelight. So, why is the study of the past today, for the most part, still constrained by the 19th-c. conventions of hand-drawn plans, static photos, and long descriptive lists? I'm not saying that those things are bad; I'm saying that we've moved on.

Understanding the distant past isn't easy; we weren't there! Archaeology (the study of the material culture of the past) emerged in the age of fine draftsmanship, meticulously refined renderings crafted slowly by hand, and equally elaborate prose (see sample 18th c. renderings at the left; hover over to enlarge). But that was centuries ago, and you don't see many people these days riding in horse-drawn carriages, writing books with quill pen, or finding their way by candlelight. So, why is the study of the past today, for the most part, still constrained by the 19th-c. conventions of hand-drawn plans, static photos, and long descriptive lists? I'm not saying that those things are bad; I'm saying that we've moved on.

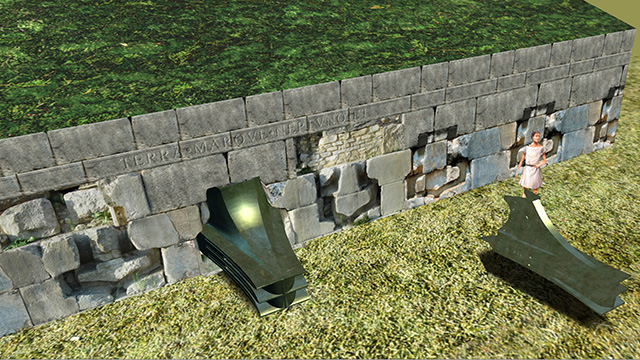

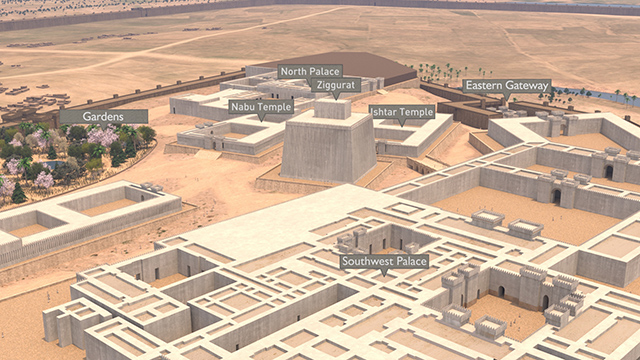

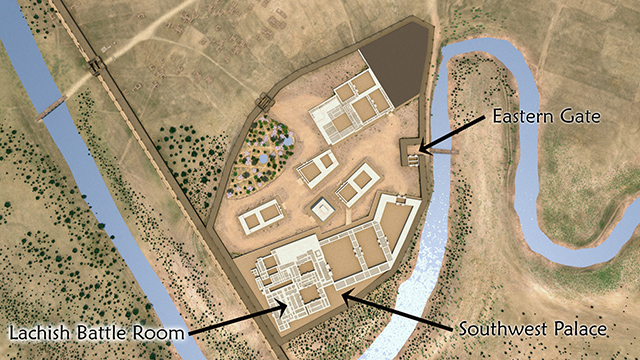

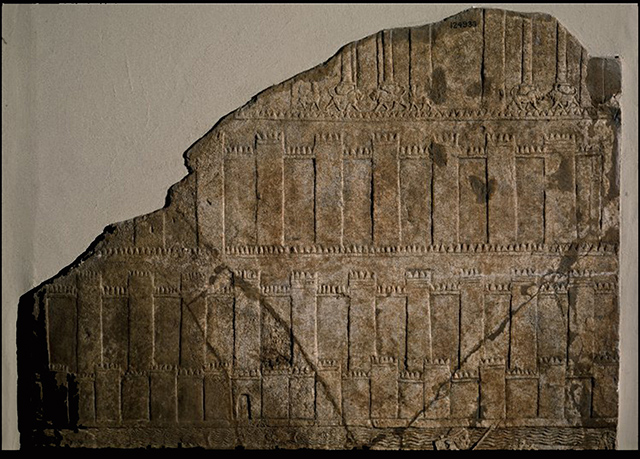

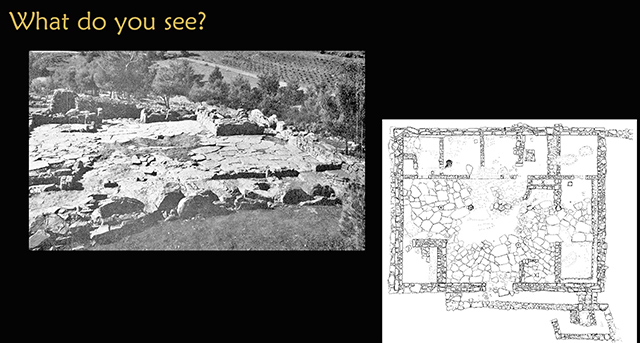

Further, classes teaching archaeology using slides often find that students have difficulty deciphering ancient sites from only plans and views (what do you see at the left? hover over to enlarge). Even archaeologists have trouble interpreting a scatter of rocks, let alone envisioning how ancient people lived and used these sites.

Further, classes teaching archaeology using slides often find that students have difficulty deciphering ancient sites from only plans and views (what do you see at the left? hover over to enlarge). Even archaeologists have trouble interpreting a scatter of rocks, let alone envisioning how ancient people lived and used these sites.

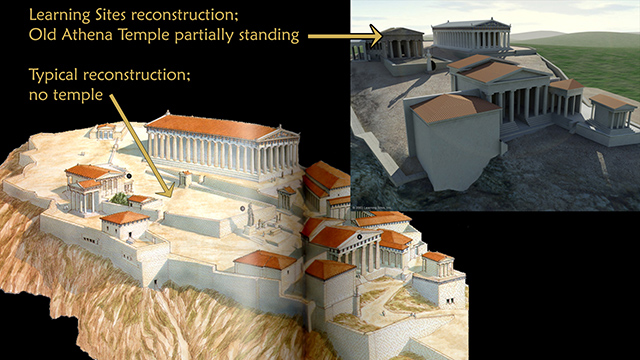

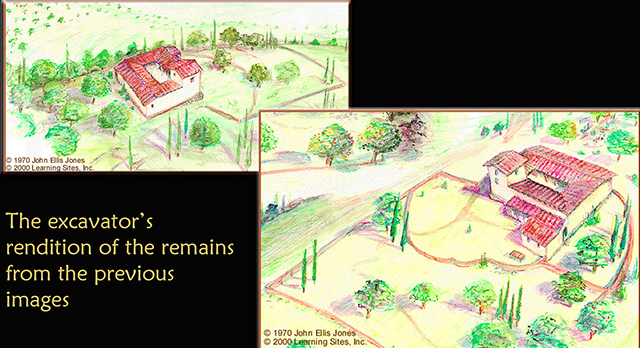

Artists' impressions offer some additional information, but there must be a better way to teach history, test hypotheses, and validate interpretations. It took a while for computers to catch up our visualization wishes (the excavator's own reconstruction sketches at the left; images courtesy of J. E. Jones; hover over to enlarge).

Artists' impressions offer some additional information, but there must be a better way to teach history, test hypotheses, and validate interpretations. It took a while for computers to catch up our visualization wishes (the excavator's own reconstruction sketches at the left; images courtesy of J. E. Jones; hover over to enlarge).

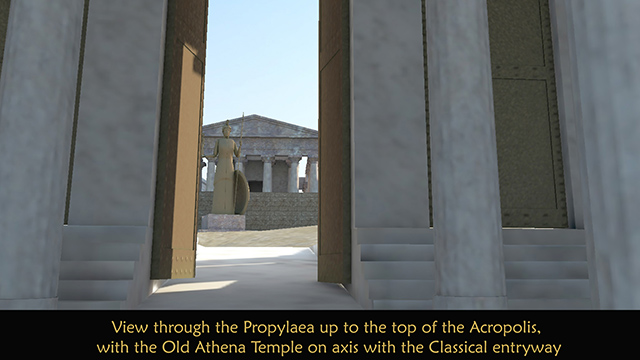

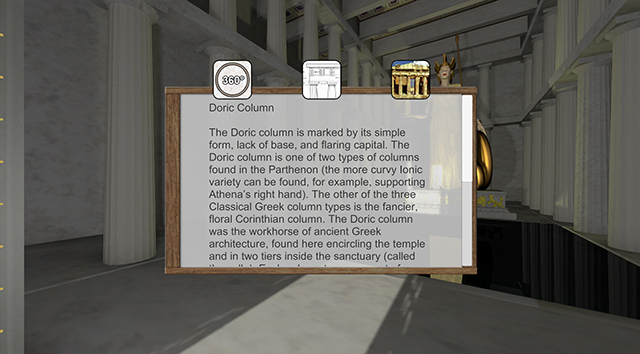

But now we can appreciate ancient places in ways that approximate the viewpoints of the original inhabitants, using virtual reality (sample renderings from the Learning Sites virtual reality model of the Vari House; hover over to enlarge; to take a real-time virtual tour of the Vari House, see the Learning Sites homepage).

But now we can appreciate ancient places in ways that approximate the viewpoints of the original inhabitants, using virtual reality (sample renderings from the Learning Sites virtual reality model of the Vari House; hover over to enlarge; to take a real-time virtual tour of the Vari House, see the Learning Sites homepage).

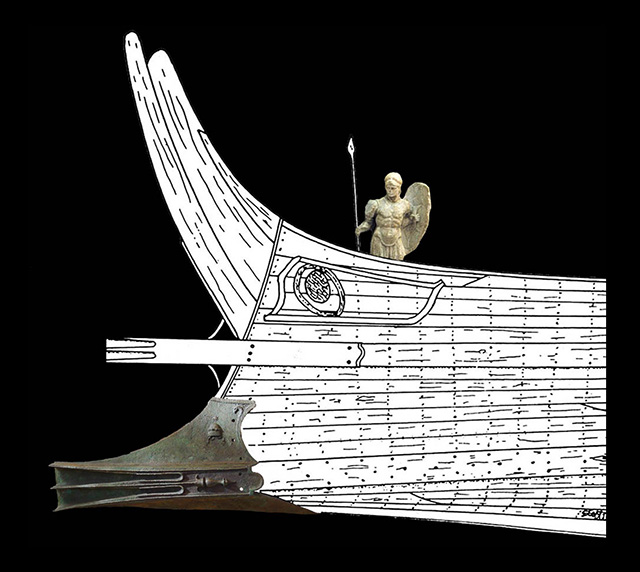

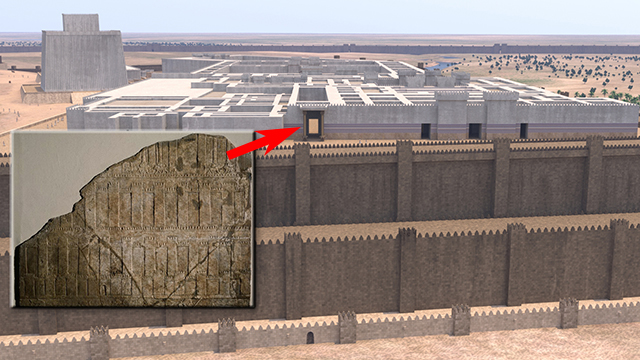

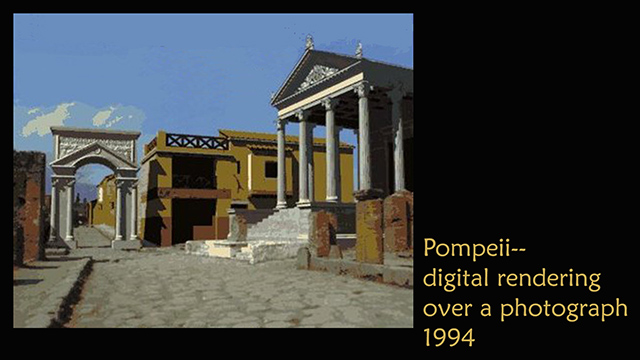

Already by the 1980s, computers were helping us visualize archaeological finds, mostly by way of low-resolution 3D models of small objects. As software improved, entire buildings and sites could be digitally reconstructed with the 2D output renderings enhanced using image-editing tools (see a example of an early digital reconstruction at the left; hover over to enlarge). A leap in capability occurred in the early 1990s when virtual reality left the lab and hit mainstreet -- but at a price. Viewing virtual worlds in the 1990s required million-dollar computer workstations and graphics cards the size of refrigerators.

Already by the 1980s, computers were helping us visualize archaeological finds, mostly by way of low-resolution 3D models of small objects. As software improved, entire buildings and sites could be digitally reconstructed with the 2D output renderings enhanced using image-editing tools (see a example of an early digital reconstruction at the left; hover over to enlarge). A leap in capability occurred in the early 1990s when virtual reality left the lab and hit mainstreet -- but at a price. Viewing virtual worlds in the 1990s required million-dollar computer workstations and graphics cards the size of refrigerators.

Today VR can be enjoyed on laptops, smartphones, and numerous low-cost headsets of increasing fidelity (such as with the gear pictured at the left; hover over to enlarge). Virtual reality is interactive, self-directed, real-time navigation through a computer-generated 3D space that displays a synthetic scene. When this technology was embraced by a few innovators in the early 1990s, digital archaeology spawned virtual heritage. Virtual heritage, then, is the use of virtual reality technologies for the visualization of the past. After all, since the past happened in 3D and in color, that's how it should be studied, taught, and published! And, interactive 3D computer models permit more innovative inquiries than are possible when using traditional 2D paper-based media.

Today VR can be enjoyed on laptops, smartphones, and numerous low-cost headsets of increasing fidelity (such as with the gear pictured at the left; hover over to enlarge). Virtual reality is interactive, self-directed, real-time navigation through a computer-generated 3D space that displays a synthetic scene. When this technology was embraced by a few innovators in the early 1990s, digital archaeology spawned virtual heritage. Virtual heritage, then, is the use of virtual reality technologies for the visualization of the past. After all, since the past happened in 3D and in color, that's how it should be studied, taught, and published! And, interactive 3D computer models permit more innovative inquiries than are possible when using traditional 2D paper-based media.

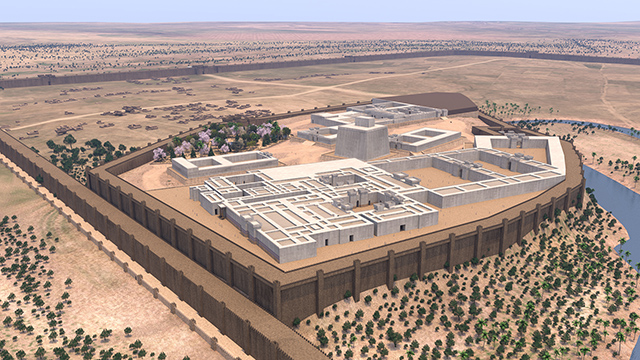

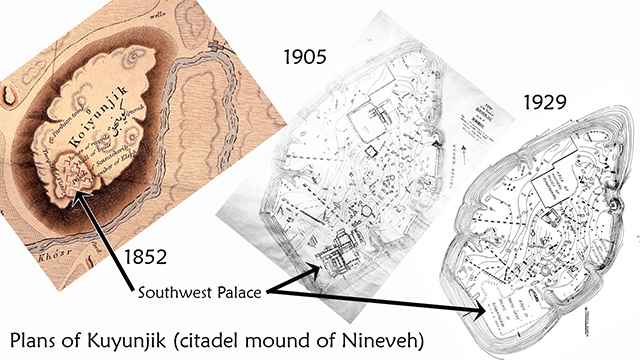

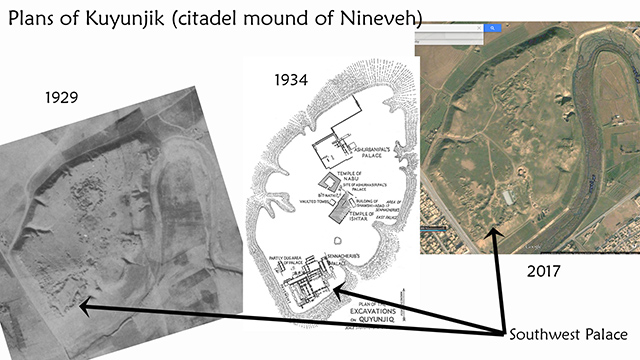

My company, Learning Sites, digitally reconstructs sites, buildings, artifacts, and events for archaeologists, museums, schools, publishers, antiquities services, and broadcast. We're the oldest company in the world dedicated to virtual reality-based archaeological education and research, working to bring history to life through vivid visualizations of the past re-created to the highest standards of scholarship. To complement today's other presentations, I'll discuss virtual heritage, some projects that we've modeled over the past 25 years, with a focus on our work at Nineveh, and conclude with a glimpse at a paradigm shift about to hit archaeological fieldwork.

My company, Learning Sites, digitally reconstructs sites, buildings, artifacts, and events for archaeologists, museums, schools, publishers, antiquities services, and broadcast. We're the oldest company in the world dedicated to virtual reality-based archaeological education and research, working to bring history to life through vivid visualizations of the past re-created to the highest standards of scholarship. To complement today's other presentations, I'll discuss virtual heritage, some projects that we've modeled over the past 25 years, with a focus on our work at Nineveh, and conclude with a glimpse at a paradigm shift about to hit archaeological fieldwork.